Governments Gone Wild

Frank and Mike look into some history regarding false flags and evil governments. From Revolutionary Cuba to Nazi Germany and back, the machinations of dishonest governments never seem to end. So the question remains, why do we trust the government(s) in the modern age? Join us on a journey that is less speculation than actual proof, that your very own government is acting overtly and directly against your interest in freedom and peace. All about them facts, no hyperbole.

All this and more is available here at your fingertips in what we call ‘light video format’ (accompanying photos and videos) on YouTube and in audio/podcast format on Soundcloud!

DON’T FORGET TO LIKE AND SHARE TO HELP SPREAD THE WORD — LEAVE US COMMENTS AND FEEDBACK

https://www.gaia.com/lp/content/do-you-know-how-to-identify-a-false-flag-event/

A false flag is an action carried out by a person or group, like a government or cabal, that is blamed on someone else to achieve a subversive goal. False flags pose as imminent threats to the security of a populace, when in fact they’re usually committed by that group’s own government.

False flag conspiracy theorists are often derided as being overly paranoid, fear-mongering, and irrational, and sometimes rightfully so. But when it comes to being suspicious of a potentially deceitful authority, that skepticism should be warranted; especially if there is a historical precedence. And often theories about government operations that sound the most heinous or absurd are those where the most scrutiny should be applied.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reichstag_fire

The Reichstag fire was an arson attack on the Reichstag building (home of the German parliament) in Berlin on 27 February 1933, just one month after Adolf Hitler had been sworn in as Chancellor of Germany. The Nazis stated that Marinus van der Lubbe, a Dutch council communist, was found near the building. The Nazis publicly blamed the fire on communist agitators in general, although in a German court in 1933, it was decided that Van Der Lubbe had acted alone, as he claimed to have done. After the fire, the Reichstag Fire Decree was passed. The fire was used as evidence by the Nazi Party that communists were plotting against the German government. The event is seen as pivotal in the establishment of Nazi Germany.

The fire started in the Reichstag building, the assembly location of the German Parliament. A Berlin fire station received an alarm call that the building was on fire shortly after 21:00.[1]:26–28 By the time the police and firefighters arrived, the main Chamber of Deputies was engulfed in flames. The police conducted a thorough search inside the building and found van der Lubbe. He was arrested, as were four communist leaders soon after. Hitler urged President Paul von Hindenburg to pass an emergency decree to suspend civil liberties and pursue a “ruthless confrontation” with the Communist Party of Germany. After passing the decree, the government instituted mass arrests of Communists, including all of the Communist Party parliamentary delegates. With their bitter rival communists gone and their seats empty, the Nazi Party went from being a plurality party to the majority, thus enabling Hitler to consolidate his power.

In February 1933, three men were arrested who were to play pivotal roles during the Leipzig Trial, known also as the “Reichstag Fire Trial”: Bulgarians Georgi Dimitrov, Vasil Tanev and Blagoy Popov. The Bulgarians were known to the Prussian police as senior Comintern operatives, but the police had no idea how senior they were: Dimitrov was head of all Comintern operations in Western Europe. The responsibility for the Reichstag fire remains an ongoing topic of debate and research. Historians disagree as to whether van der Lubbe acted alone, as he said, to protest the condition of the German working class. The Nazis accused the Comintern of the act. Some historians endorse the theory, initially proposed by the Communist Party, that the arson was planned and ordered by the Nazis as a false flag operation. The building remained in its fire-damaged state until it was partially repaired from 1961 to 1964, then completely restored from 1995 to 1999.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Maine_(ACR-1)

In January 1898, Maine was sent from Key West, Florida, to Havana, Cuba, to protect U.S. interests during the Cuban War of Independence. Three weeks later, at 21:40, on 15 February, an explosion on board Maine occurred in the Havana Harbor (coordinates: 23°08′07″N 82°20′38″W). Later investigations revealed that more than 5 long tons (5.1 t) of powder charges for the vessel’s six- and ten-inch guns had detonated, obliterating the forward third of the ship. The remaining wreckage rapidly settled to the bottom of the harbor. Most of Maine‘s crew were sleeping or resting in the enlisted quarters, in the forward part of the ship, when the explosion occurred. In total, 260 men lost their lives as a result of the explosion or shortly thereafter, and six more died later from injuries. Captain Sigsbee and most of the officers survived because their quarters were in the aft portion of the ship. Altogether there were 89 survivors, 18 of whom were officers. On 21 March, the U.S. Naval Court of Inquiry, in Key West, declared that a naval mine caused the explosion.

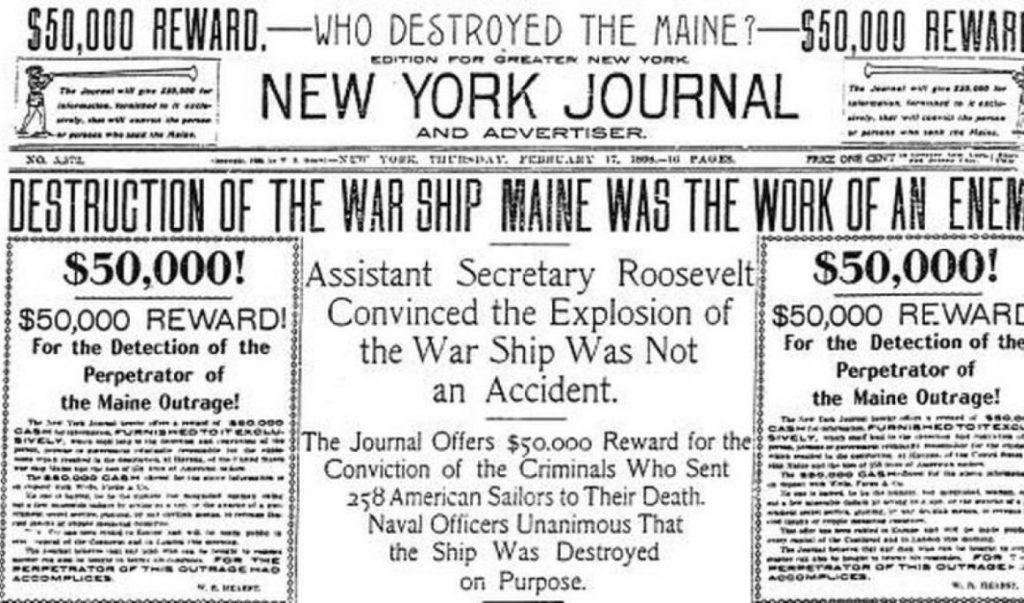

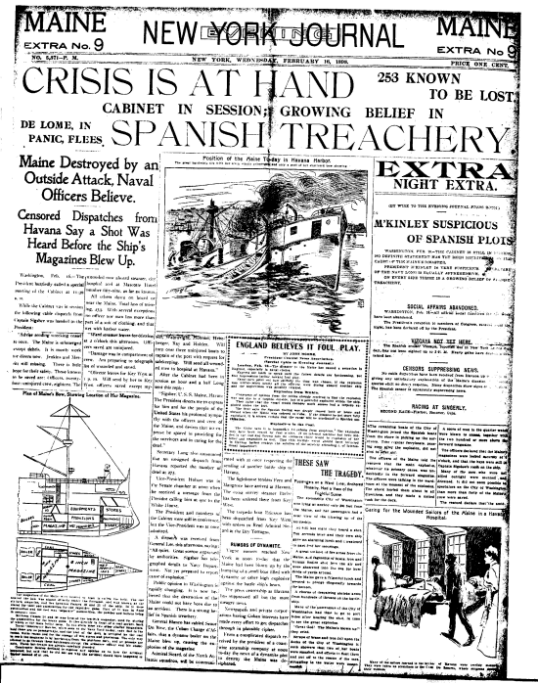

The New York Journal and New York World owned respectively by William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer, gave Maine intense press coverage, but employed tactics that would later be labeled “yellow journalism.” Both papers exaggerated and distorted any information they could attain, sometimes even fabricating news when none that fit their agenda was available. For a week following the sinking, the Journal devoted a daily average of eight and a half pages of news, editorial, and pictures to the event. Its editors sent a full team of reporters and artists to Havana, including Frederic Remington, and Hearst announced a reward of $50,000 “for the conviction of the criminals who sent 258 American sailors to their deaths.” The World, while overall not as lurid or shrill in tone as the Journal, nevertheless indulged in similar theatrics, insisting continually that Maine had been bombed or mined. Privately, Pulitzer believed that “nobody outside a lunatic asylum” really believed that Spain sanctioned Maine‘s destruction. Nevertheless, this did not stop the World from insisting that the only “atonement” Spain could offer the U.S. for the loss of ship and life, was the granting of complete Cuban independence. Nor did it stop the paper from accusing Spain of “treachery, willingness, or laxness” for failing to ensure the safety of Havana Harbor. The American public, already agitated over reported Spanish atrocities in Cuba, was driven to increased hysteria.

Maine‘s destruction did not result in an immediate declaration of war with Spain. However, the event created an atmosphere that virtually precluded a peaceful solution. The Spanish–American War began in April 1898, two months after the sinking. Advocates of the war used the rallying cry, “Remember the Maine! To hell with Spain!” The episode focused national attention on the crisis in Cuba but was not cited by the William McKinley administration as a casus belli, though it was cited by some already inclined to go to war with Spain over perceived atrocities and loss of control in Cuba.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Northwoods

Operation Northwoods memorandum (13 March 1962)

Lyman L. Lemnitzer, who was in charge as the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

Operation Northwoods was a proposed false flag operation against the Cuban government that originated within the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) and the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) of the United States government in 1962. The proposals called for the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) or other U.S. government operatives to commit acts of terrorism against American civilians and military targets, blaming it on the Cuban government, and using it to justify a war against Cuba. The plans detailed in the document included the possible assassination of Cuban émigrés, sinking boats of Cuban refugees on the high seas, hijacking planes, blowing up a U.S. ship, and orchestrating violent terrorism in U.S. cities. The proposals were rejected by the Kennedy administration.

At the time of the proposal, communists led by Fidel Castro had recently taken power in Cuba. The operation proposed creating public support for a war against Cuba by blaming it for terrorist acts that would actually be perpetrated by the U.S. Government. To this end, Operation Northwoods proposals recommended hijackings and bombings followed by the introduction of phony evidence that would implicate the Cuban government. It stated:

The desired resultant from the execution of this plan would be to place the United States in the apparent position of suffering defensible grievances from a rash and irresponsible government of Cuba and to develop an international image of a Cuban threat to peace in the Western Hemisphere.

Several other proposals were included within Operation Northwoods, including real or simulated actions against various U.S. military and civilian targets. The operation recommended developing a “Communist Cuban terror campaign in the Miami area, in other Florida cities and even in Washington”.

The plan was drafted by the Joint Chiefs of Staff, signed by Chairman Lyman Lemnitzer and sent to the Secretary of Defense. Although part of the U.S. government’s anti-communist Cuban Project, Operation Northwoods was never officially accepted; it was authorized by the Joint Chiefs of Staff, but then rejected by President John F. Kennedy. According to currently released documentation, none of the operations became active under the auspices of the Operation Northwoods proposals.